- Home

- Laura Anne Gilman

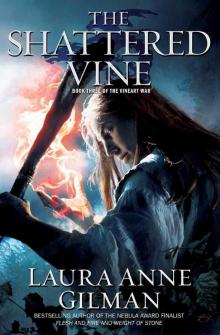

The Shattered Vine

The Shattered Vine Read online

Thank you for purchasing this Gallery Books eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Gallery Books and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

THE SHATTERED VINE

Also by Laura Anne Gilman from Gallery Books

Flesh and Fire

Weight of Stone

Gallery Books

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2011 by Laura Anne Gilman

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Gallery Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Gallery Books hardcover edition October 2011

GALLERY BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Renata Di Biase

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gilman, Laura Anne.

The shattered vine / Laura Anne Gilman.—1st Gallery Books hardcover ed.

p. cm. — (The vineart war ; bk. 3)

1. Magic—Fiction. 2. Vineyards—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3557.I4545S53 2011

813'.54—dc23

2011024966

ISBN 978-1-4391-0148-3

ISBN 978-1-4391-2690-5 (ebook)

For Geoff, who will read this,

and my twinling, who probably won’t.

You guys have been my sanity

and my lifeline while I wrote this,

and I love ya.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Prologue

Part 1

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Part 2

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part 3

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Over the course of these three books, so many people have stepped forward with information and advice, help and support, that at this point thanking them all individually would require another chapter, and my editor informs me the book is Quite Long Enough, thank you.

Thank you. All of you. For your answers, for your patience, and for sharing your enthusiasm not only for the final product but the process of winemaking. You are all magicians.

However, the trilogy cannot come to a close without again acknowledging The Jens—my agent, Jennifer Jackson, and my editor, Jennifer Heddle. Through trial and triumph, panics and partying . . . you guys rock.

Truth, history, legend . . . they are all the same. The Washers, our self-appointed guardians, tell us a story, a lovely story, about gods and sacrifice, of the role that Vinearts play and what they may and may not do, to keep the world safe and whole.

I am neither Vineart nor Washer, but solitaire. I view the world down the line of my blade, not softened by legends of some demigod long dead and gone. Nor am I tied to the promises of a place or liege, to watch my fortunes rise and fall by how well my master weaves his strands of power. Solitaires give up House and hearth, have no allegiances save to ourselves and whatever oaths of employment we take. That allows us to see the world as it is, entire, and to hear much that would otherwise remain unspoken, or mis-said.

For history is written by the survivors, and each side has their version to tell. When you have no stake in choosing sides, if you pry away the gilding and the pretty words and look down the edge of your blade, what remains is this: that in the years before modern reckoning, a plague attacked the vineyards of the prince-mages, twisting and changing the fruit—and the magic within. Call it Sin Washer’s blood, or the wrath of the gods, or merely a ferocious blight as comes by chance, it spread too quickly to be halted, too fiercely to be treated. What had been, was no more.

The prince-mages, who depended on magic to hold power, took their fear out on the people, and their cruelty became legend. Eventually the people rebelled, tearing down the vineyards and destroying the Houses of power. . . .

And the entire world suffered, because order was out of order. The Emperor died, the empire crumbled, and the lands were left to their own devices. I can only imagine the suffering that must have followed; the history books do not speak of it, and the Washers would pretend it never happened.

Slowly, over decades, the people and the princes came to an understanding. The magic passed into the hands of those chosen not from the ranks of power, but the children of the common populace, while physical might remained in the hands of the princes, and peace settled . . . or as much peace as man, ever restless, can know.

And thus the world moved on. Generations were born and died, towns grew into cities, armies marched, kings and princes rose and fell, some lands prospered while others faded . . . while on their plots of land the Vinearts tended to their vines and worked their magic, isolated from the strife and innocent of those cycles of power. The world remained steady, the gods no longer putting their hands into the affairs of mortals. We began to believe that this was as it always would remain.

We cannot choose the age we live in. The world of my youth was a simpler one—or perhaps I merely believed it to be so. But simplicity is not the natural state of affairs for man, and the whispers of past glory—real or otherwise—are forever in our ears.

I have been on the road nearly half my life, taking the blade the year I turned sixteen. I had thought I would end my service an old woman, with only small stories to tell.

Instead, I found myself on the outskirts of a great story, and was forever changed.

A year past, I accepted a commission to travel with a group of Washers, to bear them company, and protect them from the dangers of the road. Such men should not need my protection, not within the boundaries of the Lands Vin, and I wondered at it, but they were a cheerful group, eager to serve and share their learning, and I merely assumed they carried something of great worth in their packs, and wished to be certain.

But by the end of those two weeks, another Washer joined them, and the mood darkened. It was then I first heard the rumor of a violence growing deep underfoot, reaching its tendrils into the hearts and souls of princes and Vinearts alike . . . stirring the discord that had been settled long ago.

It was then that I first heard the name Malech. The first time I heard of the Apostasy. It would not be the last. Suddenly the ground under our feet was no longer steady, the tools in our hands no longer trusted, the world no longer safe.

A storm approached, and the winds whispered one word: magic.

I a

m a solitaire. I know that the road is dangerous, that my blade is meant to draw blood, even if it never does. Unlike Vinearts, we see who we strike at, know the damage we do with our skills. I did not envy them their lives, tied to one place and bound by such rules . . . but I sorrowed to see that innocence die.

Prologue

Prince Diogo was a cautious man. He took no action without considering the benefits and potential deficits, and thought things through the long-term. But the moment he first heard rumors of a Vineart who challenged tradition, undermining the Commands the Washers had shoved down their throats for centuries, he had known what it meant, and what he needed to do.

The Iajan land-lord was not a particularly superstitious man; he did not keep faith with the Silent Gods, and had no trust in any demigod who was fool enough to die. His sole faith and concern was with the land he had been born to, the title his family had held for seven generations, since the old duque had been slain in his sleep like the last emperor of Ettion and for much the same reasons.

Every action Diogo took, he did for Iaja, for its glory and its defense. His portion of it, anyway.

So while most landlords chose to meet their visitors in grand halls, richly appointed and designed so that the supplicant was at a disadvantage, knew his place, and understood that all the power in that room resided with its owner, Diogo did not bother. He wanted those who came to stand before him focused on his words, not the richness of their surroundings, and he made no pretense otherwise.

For that reason, his meeting hall was a small, almost ordinary space, with three small windows set along the upper half of the wall to let in clear bands of sunlight during the day, and magelights flanking the other three walls for when darkness fell. The afternoon sun was fading now, but it still picked out the rich red hues of the table they sat at, catching at the inlaid mother-of-pearl designs. Richly appointed, yes, but somber, by most traditionally flamboyant Iajan standards. But this day, this meeting, Diogo had invited the first man to sit at the table with him, as though equals.

Vineart Ranji did not let himself believe it. His yards might be sacrosanct, but they were ringed by the land-lord’s villagers, who in turn were caught between the crush and the fox in terms of who they could support, and who they need fear. Diogo had the power here.

But Ranji was seated, unlike the third man standing at the far end of the table, staring at them as though they had lost their wits.

“You cannot mean this.” His voice was that of a well-educated man, controlled, melodious, and filled with shock.

“I do not say things I do not mean.” In keeping with his surroundings, Diogo did not drawl his words, or practice the play-stalk of cats in his speech. Nor did he pretend unconcern or ignorance of what he was doing. This land-lord played the game, no denying it, but he did it with an honesty that Ranji found both disturbing and oddly disarming. You knew what trouble you were in when you dined with him.

Of all the lords in Iaja, when every soul knew that the lords had been in collusion, only Diogo did not deny placing the bounty on Master Vineart Malech’s head to keep him from interfering with things—matters of power—beyond his concern. Only Diogo, after things went to ashes and rot, had not tried to hide behind tradition, but stood straight and said that he would do whatever was needful to protect what was given to him.

Common knowledge, among those who listened, that Diogo was dangerous to those he considered the enemy.

That was why Ranji had accepted his offer of Agreement, although he had refused similar overtures from the other Iajan lords. If you must choose among evils, choose an evil that admits itself. That way, you knew where you stood, and you could stand out of its way.

It was a pity, Ranji thought, that more of the world was not so forthright.

“This is unacceptable,” the third man said, drawing his red robes about him, his left hand falling to rest on the wooden cup hanging from his belt. The closely trimmed beard adorning his swarthy chin seemed to quiver in indignation. “Surely you know that this is not allowed.”

“There is much that is not allowed,” Diogo said. “And much that happens nonetheless. So unless your prayers and invocations can prevent crops from failing overnight, villages from being ravaged by beasts, and men disappearing without a trace, then I suggest you leave the work to those of us willing to act, and go Wash something instead.”

It was said lightly, but it was no joke, and the Washer stiffened again, this time in rage rather than confusion. “The Collegium will hear of this!”

Diogo stood, then, his temper finally frayed, and Ranji flinched, although the anger was not directed at him. “The Collegium has heard of this. Over and over again, for a year and more now, we have told them what is happening, warned them, and begged for advice, for some kind of guidance.” He regained control of himself, tempering his anger into sadness and reproach. “We begged you for help when the sickness took our children, when the hives withered and died.” The sadness slipped, revealing anger once again. “And all we received in response was the repeated droppings of Sin Washer’s Commands, that we sit back and be patient, that the balance held, that all would be well, if we only trusted in Sin Washer’s Solace.”

Ranji lowered his gaze to the table, his fingers laced together in his lap. He would not speak against the Brotherhood, but he could not defend them, either. Diogo had the right of it. Once Malech had pulled that curtain aside, exposed the threat to their very existence, it had become impossible to not-see, to not-hear. Isolation was not protection.

“There is no more Solace in the world, Washer,” Diogo said, more quietly now. “The Heirs are impotent, and now it is time for those with power to use it. Together, if that will accomplish our means.”

The Washer turned to Ranji as though to implore sanity from him. “You cannot . . .”

“Cannot?” Diogo did not give Ranji the opportunity to respond, forcing the Washer’s attention back to him. “Will you stop us all, Washer? Keep us from saving the people entrusted to our care? Will you stop the people themselves when, in their panic, they turn on you as well, having already destroyed the Great Houses?”

The Washer shook his head, denying such a possibility. “It is not that bad . . .”

“It is worse.”

The conversation, such as it had been, was over. The lord barely turned, but the subtle jerk of his chin was enough for the two figures standing, almost lazily, at the doorway. Firm hands were laid upon the Washer’s arms, and he was led—not ungently—out of the chamber.

“We’re sorry, sahr.” The voice was low, but not soft; the woman might have been apologizing, but she was not going to refuse her orders. A solitaire, one of the hire-women fighters. Not young, with strands of gray in her dark hair, and a strong, pointed chin with a thin white scar across the tip; she had an air of determined patience about her. Her companion-in-arms wore Diogo’s brand on his leather cuirass, rather than her simple star-sigil, and his hand held more tightly, as though worried that he might be judged were the Washer somehow to escape. A slender, brownish hound padded behind them, its dark eyes fixed on the Washer but its attention focused on the solitaire, awaiting her command even as it guarded her back.

The Washer addressed his words to the woman, judging the lad beyond any common sense, his loyalty too deeply ingrained. “You know what they do . . . it is an abomination against all decency. This entire city will—”

“This entire city is the only safe spot on the coastline,” the solitaire retorted. “Sahr Washer, you are no fool. Diogo spoke only truth. The Collegium had its chance, and they wasted it, and now the people look to another to save them. You, your people, gave him this power; he did not take it.”

They were in the hallway proper now, and she released his arm, shooting a glare at her companion until he followed suit. “Go back inside,” she told the young man in a low voice. “I will see the Washer to the door.”

The Washer had not been offered quarters when he arrived, as was traditional,

nor given the chance to break his travel with a meal, or even to rinse his mouth with vin ordinaire. At the time, he had been too intent on the message he had been sent to deliver. Now, spent and tossed aside, he felt his exhaustion.

He would ask no favors of this apostate House, however.

They walked in silence through the hallway: two humans and the hound, the gray stone floors echoing their footsteps, the usual flow of foot traffic normal to a Great House absent.

“How bad is it, Daughter of the Road?”

“Bad.” She did not hesitate, or ask him what he meant. “The past ten-month, it seems all has gone wrong or worse, but no one can lay finger on the cause or find any pattern. Lacking specific action or remedy, the people worry, chewing at themselves and any others they can reach. There are rumors in the street, and rumors in the powdered baths, and the rumors are the same. Something rises out of the seas and falls from the skies, crawls from the dirt and covers us while we sleep, invisible and with malign intent. Surely you have heard the same?”

He did not respond to her question. “And your hire-lord?”

The solitaire did hesitate, then. “A good man, as such men go. Strong, and looking to become stronger, always playing his own political games, but with cause and an eye to the long road. No more or less than any man of power. The Vineart with him”—she shrugged, but without a hitch in her stride or allowing him to pause—“the Vineart does what he must to survive, Brother, as do we all.”

He might have argued the point, but arguing with a solitaire was the act of a fool: they did not care.

The guards at the main entrance watched them go, cautious but incurious, and they passed across the stone courtyard toward the front gate and the city beyond. There were more people gathered here, waiting their turn to see some official or another, or merely lingering to find the morning’s gossip. The conversations were hushed but lively, the scene vibrant, and for a moment both Washer and solitaire could pretend that it was a normal day, that nothing was wrong, that everything, once they passed through the gates, would be well.

West Winds' Fool and Other Stories of the Devil's West

West Winds' Fool and Other Stories of the Devil's West Gabriel's Road

Gabriel's Road Morgain's Revenge

Morgain's Revenge The Shattered Vine

The Shattered Vine Laura Anne Gilman - Tales of the Cosa Nostradamus

Laura Anne Gilman - Tales of the Cosa Nostradamus The Camelot Spell

The Camelot Spell VISITORS

VISITORS Staying Dead

Staying Dead Silver on the Road

Silver on the Road Weight of Stone

Weight of Stone Promises to Keep

Promises to Keep Tricks of the Trade psi-3

Tricks of the Trade psi-3 Blood from Stone

Blood from Stone Soul of Fire tp-2

Soul of Fire tp-2![Pack of Lies [2] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/pack_of_lies_2_preview.jpg) Pack of Lies [2]

Pack of Lies [2] Burning Bridges

Burning Bridges The Work of Hunters

The Work of Hunters Miles to Go

Miles to Go Pack of Lies psi-2

Pack of Lies psi-2 Tricks of the Trade

Tricks of the Trade Hard Magic

Hard Magic Bring It On

Bring It On Darkly Human

Darkly Human The Cold Eye

The Cold Eye An Interrupted Cry

An Interrupted Cry Soul of Fire

Soul of Fire Hard Magic psi-1

Hard Magic psi-1 The Shadow Companion

The Shadow Companion Flesh and Fire

Flesh and Fire