- Home

- Laura Anne Gilman

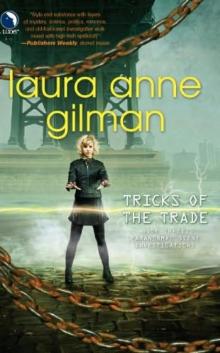

Tricks of the Trade Page 21

Tricks of the Trade Read online

Page 21

Nifty, to contrast, perched himself on the edge of the wood table and leaned forward to talk to our suspect, his body language going for the big-man-to-big-man thing. I leaned against the now-closed door, my arms loose by my side, and looked at the minotaur, trying to channel Stosser’s best “I know something you don’t want me to know” expression, which mainly involved a perfectly emotionless face that still managed to smirk. The smirk was easier than holding my arms loose. Now I understood why Venec crossed his arms when he leaned; it helped you balance.

“He’s dead.”

No surprise. No reaction at all. Not that it was easy to tell, on that bull head, but not even his ears twitched.

“You and he had some words. You wanted him to stop bitching about the company that wasn’t paying him, Elliot Packing.”

The bull shrugged, and on him the gesture looked less like, in J’s words, “an inelegant expression of uselessness,” and more of a threat. “Wasn’t just me wanted him to shut up. He opened his mouth, and work dried up. They didn’t know one beast from another, so they stopped hiring us all.”

“And you put an end to that.”

“You’re the pups, you tell me.”

Interesting. We hadn’t identified ourselves. I felt a pulse of interest and—amusement?—coming from Venec, while Nifty frowned. This was changing the plan a little. I reached down and pulled up some extra current, playing the neon-bright strands between my mental fingers, remembering Nicky’s cat’s cradle, keeping the current cool but limber, ready for anything.

Fatae were magic, could sense magic, they didn’t use magic. I kept repeating that to myself, even as Nifty picked up the change in direction and ran with it.

“How did you get him into the river?”

The minotaur looked at Nifty like he was insane. “I threw him.”

Venec laughed. “Ask a stupid beast, get a stupid answer.”

That wasn’t to the script, either; Ben was trying to rile the minotaur, get it to attack him, so we’d have an excuse to take it down. My guys all had death wishes.

“You’re admitting that you killed Aodink?” Nifty asked, pulling the bull’s attention back to him.

“I ain’t admitting nothing. Threw him in the river, is all.”

“Yeah, well, you’re not smart enough to figure out that if you shut Aodink up, the work would start to flow again,” Nifty said. “So who gave you the orders?”

That wasn’t going to work; I could tell already. The minotaur wasn’t ashamed of being bottom of the brain-pile; that was just the way the breed was; strong but not built for cognitive functions. And it wasn’t intimidated by current, either. We weren’t going to get an admission of the actual killing, and he wasn’t going to attack us, either; he was dumb but not a fool.

“You were used,” I said, totally breaking the plan. I was supposed to watch, not talk. “You were used and then set up to take the fall, just like your ancestor. And for nothing. The jobs aren’t coming back, cousin. Elliot Packing has already moved on, hired other people to do their work. Bought machinery that can go 24/7, without being fed, without giving back talk. Machinery that humans will work—legal, licensed humans, not fatae.”

I was using everything I’d heard from Danny and Bobo, playing into the worst fears of the fatae underground; of being replaced not with others of their kind, but humans, the majority population, with legal papers and legal standing. I did it, knew I was doing it, hated myself for doing it, and did it, anyway.

“They said…” the minotaur blurted, and then stopped. But Nifty caught whatever it was he wasn’t saying.

“They said if you took one for the team, it would all go back to the way it was before? Do this for them, and they’d take care of you? All one team, working for the same goal, and everyone has a specific job….”

“All I had to do was take him down and throw him in,” the minotaur said, like he was complaining. “That was all. Then they’d hire us all back.”

It was so sad I was almost angry. At the fatae for believing, at the humans who had manipulated them, at the world where fatae had to work in the shadows, taking this kind of crap, killing their own just to survive.

“But they didn’t,” Nifty said.

“They didn’t call. It’s been days, and they haven’t called.” The minotaur sounded aggrieved.

Venec glanced at me, and I nodded. My ability to run cool with my current was paying off; I had the minotaur’s voice down on tape, the small recorder hidden in the leg pocket of my pants. It wouldn’t hold up in a Null court of law, but it didn’t have to. We were hired to find out the truth of an event, without worrying about right or wrong. It wasn’t a perfect system, but it was better than what used to exist, where even if someone asked who-what-why, they couldn’t get an answer because too many people were invested in Talent being above the law. Like my dad’s killer, still walking around, unpunished.

I had a more-than-suspicion that Stosser’s grand plan involved actual courts of enforcement, someday. But that wasn’t my headache.

Right now, my headache was in front of me, starting to radiate faint tremors of pain. The drugs were wearing off. We had what we needed; now it was time to go.

*enough* I sent to Nifty, a sense of finality and a tinge of urgency, with the flavoring of Venec. I wasn’t sure how much of that he actually picked up, but it was enough.

“Don’t go anywhere,” Nifty told the minotaur, standing up, looking down at the fatae. He didn’t use current, not even a gleam of a spark, but he managed to project a sense of Official Doom. “If you do, we’re going to be really unhappy with you.”

We left the bull sitting on his sofa, moaning about how life wasn’t fair, and walked down to the street level in silence—me acutely aware of the fact that Venec’s pain meds were starting to fade, and he was holding that injured arm close to his chest. We made it as far as the curb, looking for a cab to flag down, before Nifty put his hand out, asking for the tape recorder.

“Hell, no,” I said. “You touch it, it will go up in sparks.” I took a few steps away from him. “In fact, get the hell away from me.”

Venec shouldered Nifty aside neatly with his good arm, giving me room to walk unmolested.

“Bonnie, the tape?”

Because he asked politely, I pulled the mini-corder out of my pocket and showed it to him, hitting the play button just enough that we could hear the minotaur’s voice rumbling, low but intelligible. I really didn’t think there was any danger; it took a couple of days of steady core-contact to kill something that low-tech, and we’d managed to get through the confrontation without active use of current. But shit happened, and even dumb tech like a tape recorder could get fried by a sudden defensive twitch.

Fortunately, I ran cool, which meant…

I stopped dead on the corner. “That’s it.”

“What?”

“The Roblin. It didn’t go after the stronger ones—it went after the weirder ones. I run cool, and Nick—oh, shit, Nick!”

I was surrounded by stronger Talent, and carefully not being active. Nick, on the other hand, was probably nose-forward right this fucking moment into tricky, weird, prone-to-chaos-anyway magic. He’d be like a carnival target to something like The Roblin.

My ping was instinctive: not to Nick, for fear of distracting him at a bad moment, but Stosser, who might be within reach—and had the power and the control to risk getting between a hacker-mage and a mischief imp.

“I need to get back,” Ben said suddenly, a faraway look in his eyes. “Bonnie….”

I felt the same sharp urgency he did, filtered through his connection to Stosser. “We’ll take the subway,” I said. “Go.”

eleven

Either intentionally or not, Venec left that faint connection open, so by the time Nifty and I made it to the office, I already knew that Nick was mostly all right, his computer was utterly fried, and while the rest of the team was nervous and edgy, and Stosser was annoyed, Venec was furious.

/> Not at Nicky, not even at the imp. He was furious at Ian, who had, as Nifty would say, sidelined him from the game, telling him that his injuries were serious enough to keep him on office-duty, same as Nifty had been. I walked into an office that was practically simmering with frustration and resentment.

Part of me wanted to avoid the entire thing, make like the others in obliviousness, just go directly to Nick, make sure he was okay, and then get my orders with the rest of the team.

I’d been raised to deal with my responsibilities, though, even when I was the only one who knew what they were. And the first responsibility, like it or not, want it or not, was getting Ian and Ben back on track.

I just wasn’t quite sure, even as I walked into the Big Dogs’ lair, how I was going to do that.

The two of them were sitting in chairs at opposite ends of the small office, glaring at each other. “Shune’s fine,” Ian said as I walked in, not even bothering to look at me. “The Roblin singed his fingers and fried his hair a bit, that’s all.”

Being a Talent means, by definition, that you can handle a load of current—and electricity—running through your body. Something that singed Nick’s fingers might have killed a Null. Stosser wouldn’t have thought of that, probably.

I knew that Venec had.

“I think our original guess was right. If The Roblin’s here to make mischief, its biggest challenge would be the ones who investigate mischief. So long as it’s targeting us, it’s not harassing others,” I said, addressing Ben’s worry first. “If we can keep it focused on us, nobody else will get hurt.”

Except maybe us. Still. Did a mischief imp, even the grandmother of imps, intend to kill? Then I thought about what some fatae considered harmless pranks, historically, and reconsidered.

“We can’t have it interfering with the ongoing investigation,” Stosser said. “You’ve probably wrapped up the body dump, and that was good work, but this break-in has already caused too much trouble. The client lied to us, hid details of the story, and nearly got Ben killed. I want to know exactly what is going on.”

“It goes for the unique,” I said, following my earlier thought. “I think that’s the trigger. That’s why me, and Nick.” I’d had time to think it through, on the subway ride back, lay it out into a semblance of a formal report. “We’re not the strongest of the pack, but our skills are unusual—I run cool so I bet that it was trying to make me angry, breaking all my stuff and getting me kicked out of my building, to see what I could do, what trouble it could cause. But Nick’s—” I paused; even among ourselves we didn’t often vocalize Nick’s skill “—Nick’s a challenge it wasn’t going to get many other places. So he’s going to be the real target…. But it might get bored, anyway. We need to find something…”

A thought struck me, and the way Ben’s head lifted, his dark eyes looking even more shadowed with exhaustion and pain, I could see the thought reached him in that exact instant.

I said it first. “If it wants something unique, something different to play with…”

“No.” Venec-voice. Boss-voice.

I didn’t let that stop me. “It makes sense. And if it’s already here, there’s no way to avoid it. We need to make it work for us, not against us.”

“Bonnie, no.” And then, suddenly, it wasn’t boss-voice anymore. “It’s too dangerous, especially without knowing how far it will go to get its jollies.”

Stosser was looking between us, his expression caught between knowing we had a juicy bone, and frustration that he didn’t have a chunk of it himself, and knowing that if he was patient, we’d work it out and then present it to him.

“If we’re ready for it, we’ll be okay.” Probably.

Venec was still shaking his head, even as I could tell he was running through how it might work. “We would have to…”

“I know.” It would require that we open the very doors we’d shut, take down the walls we’d built. Make a target of ourselves, and use the Merge as a trap.

And neither of us knew if it was a trap that we would be able to escape, if we’d be able to rebuild those walls, once The Roblin was dealt with.

The idea terrified me.

“This thing we have,” I said to Stosser, before Venec could say, absolutely, that he wouldn’t do it. “The Merge. It’s unique enough to attract The Roblin’s attention, distract it from anything or anyone else. Even more than Nick.” And Venec was higher-res than Nick and me both; he’d be better able to handle anything The Roblin might try. I’d be the weak link here, but I was willing to take the risk. Okay, not willing, but I didn’t see any other choice.

“Trick the Trickster?”

“Exactly. And when we have it caught, then we can figure out how to make it go away,” I finished, keeping one eye on Stosser to see how he would react, and the other on Venec, to see if he was going to try to stop me from pitching the plan. There was always a way to banish imps, either through magic or bribery. We just had to get the upper hand, somehow.

I expected Ben to be angry that Ian knew, since he’d been as much about keeping it quiet, for his own reasons, as I had, but he just looked resigned, which was how I felt about it—resigned, and glad it was out in the open, sort of.

“You think it would be enough?” Stosser asked, considering what I’d suggested.

“I think it’s a crap idea.” Ben’s voice was flat, low, not at all growly. I hated the sound of it, hated being the one who took the growl out of his voice, but I honestly didn’t know what else to do. The Roblin was focused on us right now, but what happened if it got distracted? How ADD were mischief imps? What happened if someone less-grounded, unaware of what was happening, was its next target? Madame was wary of The Roblin. The other Ancient had come to the office to warn us, specifically. And the unease from my scrying was still riding between my shoulders like an imp itself, telling me trouble was in the neighborhood. Not good, not good, and not good. We couldn’t look away. Not us, not now.

“You have anything less crappy?” I asked Venec, letting him see where my thoughts were leading.

He glared at me, then deflated, shaking his head. “No.”

Stosser intervened, then. “She’s right. It’s the best plan we’ve got, and allows the others freedom to continue the investigation of the ongoing cases.” I got the feeling that Stosser really didn’t give a damn about the imp—it was an annoyance to him, not a problem. Keeping our solve rate up, that was the problem.

“Yeah. Oh. And here.” I pulled the recorder out of my pocket, popped the tape and handed it to Stosser. “You might want to go play this for whoever it is needs to hear it. Incriminates the company, and our minotaur friend.”

He took the tape, his long fingers cool against mine. I swear, the guy really did have ice water in his veins. “I have no idea how this one will play out,” he admitted. “The NYPD has no authority over the fatae, and the Council will deem it a matter between the business and their employees, and no concern of theirs.”

The Council was kind of bloodless that way, no matter what region you went to, yeah.

“Don’t take it to the Council,” Venec said, and there was a faint growl back in his voice. “Take it to the local unions. Dockworkers, garbage haulers, anyone you can find.”

“Null unions?” I was surprised; Stosser looked utterly shocked.

Venec reached up to touch the bandage around his throat, and almost smiled, but it was the smile of a dog that knew it had you cornered. “My dad used to tell me that the unions were all that stood between the working schlub and indentured servitude, not out of the goodness of their heart, but because they wanted the power of those working schlubs organized to their direction, not someone else’s. Let’s see if their desire to swell the membership rolls trumps fataephobia.”

Oh. That was twisty, so very twisty. Appeal not to someone’s desire to see justice done, but to prevent anyone else from taking advantage of someone they could make mutual advantage from. I forgot, most of the time, that straight

-shooter no bullshit Benjamin Venec had a brain as devious as my mentor’s, and utterly lacked most of J’s ingrained social graces.

“It might not work,” Stosser said, tapping a finger against the back of his other hand, like a metronome for his thoughts. “But it’s definitely worth a try. If nothing else, it will bring Elliot Packing to the attention of others—and once they start looking for violations of objectionable practices, change might come.”

And that, really was why we did this gig, holding the actions of the Cosa up to the light. People—whatever their species—did shitty things to each other, for a whole range of reasons and justifications. We weren’t going to change human—or fatae—nature, but if there were consequences to those actions, then maybe it would stop them from happening again. Maybe.

Stosser stood up, my tape in his hand, and walked out of the office without another word, leaving Ben and me trying hard not to look at each other, but not able to look away.

Wow. Talk about an elephant in the room.

“You know I’m right. If this is as rare as you say it is, and we already know how much trouble it can cause, it will be like waving a red flag in front of a bull. The Roblin won’t be able to resist.”

“Bulls are color-blind, you know.”

I didn’t even bother to glare, instead reaching inside to slowly, carefully, dismantle the wall I’d built, one brick of control at a time. I wasn’t going to take it down all the way; I wasn’t quite willing to do that, not even to stop The Roblin, but enough. I could feel the pressure brushing against me, shifting against the exterior of my core, like…I couldn’t describe it; there were no words in my experience. Like waves rolling over each other, separate to the eye but not really, not in composition, water drops from one merging into the other, and then reforming….

That wasn’t right, either, but it was the visual that stuck with me, even as I could feel Ben unbuilding his own wall, coming down less like bricks than a melting sheet of ice.

The image of two lovers undressing for the first time? Really not far off the mark. That thought didn’t help my nerves any.

West Winds' Fool and Other Stories of the Devil's West

West Winds' Fool and Other Stories of the Devil's West Gabriel's Road

Gabriel's Road Morgain's Revenge

Morgain's Revenge The Shattered Vine

The Shattered Vine Laura Anne Gilman - Tales of the Cosa Nostradamus

Laura Anne Gilman - Tales of the Cosa Nostradamus The Camelot Spell

The Camelot Spell VISITORS

VISITORS Staying Dead

Staying Dead Silver on the Road

Silver on the Road Weight of Stone

Weight of Stone Promises to Keep

Promises to Keep Tricks of the Trade psi-3

Tricks of the Trade psi-3 Blood from Stone

Blood from Stone Soul of Fire tp-2

Soul of Fire tp-2![Pack of Lies [2] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/pack_of_lies_2_preview.jpg) Pack of Lies [2]

Pack of Lies [2] Burning Bridges

Burning Bridges The Work of Hunters

The Work of Hunters Miles to Go

Miles to Go Pack of Lies psi-2

Pack of Lies psi-2 Tricks of the Trade

Tricks of the Trade Hard Magic

Hard Magic Bring It On

Bring It On Darkly Human

Darkly Human The Cold Eye

The Cold Eye An Interrupted Cry

An Interrupted Cry Soul of Fire

Soul of Fire Hard Magic psi-1

Hard Magic psi-1 The Shadow Companion

The Shadow Companion Flesh and Fire

Flesh and Fire