- Home

- Laura Anne Gilman

Morgain's Revenge Page 7

Morgain's Revenge Read online

Page 7

“Sir Tawny?” she managed to croak out, but the griffin did not come to her rescue. She could not take her eyes off the sea monster long enough to look around for him.

No way to tell herself that this was all magic; that the fish could not really truly exist; that they were on solid ground, not deep in the ocean. Those teeth looked far too real, too solid. And magic could kill just as easily as an ordinary sword. All it took was intent.

Don’t be some fish’s meal, Ailis…. Merlin? A faint whisper, barely even there. She probably imagined it. No matter. She grabbed onto it, angry at the thought that the enchanter might think she would be so weak, to be taken down by a figment of magic….

“Not me! No you don’t!” she cried, throwing up her arms and closing her eyes again as the monster loomed closer, rancid breath blowing onto her skin and up her nose. The smell made her want to gag. She was overcome with disgust, swamping even the fear until all she felt was revulsion, and from that revulsion came more anger. “Get. Away. From. Me!”

A blast of fish-gut breath washed over her and…then it was gone.

Ailis opened her eyes to an empty chamber. Even the colors seemed more muted now, tinted with a pale golden light rather than the watery green of earlier.

“Rrrrrr?”

Shaking so badly she could hardly take it, Ailis reached out and found a handful of warm feathers, and the cool breath of the griffin reached over her like a benediction.

“Some help you were,” she said, using him to haul herself up off the floor. She looked around the room and shuddered.

“I almost forgot,” she said. “It’s pretty, but it’s still magic. Morgain’s magic. Nothing good can come from that.” It had been nice while it lasted, that feeling of freedom—of pleasure without price—but it was a dream, and she was awake now. Something inside her protested, but the weight of her terror, and the knowledge that nobody would save her if she could not save herself, weighed down that ambition until it sank without a trace. Ailis was a practical girl. She’d always had to be: no room for dreams in the life of a servant. That was what had saved her over and over again. It would be what saved her again now, if anything did.

She thought about going back to her room and locking the door behind her, but that didn’t seem right, either. Hiding was easy, but not always practical.

“I need to find a way out of here,” she said. “I can’t stay. I can’t let the dream make me forget.” There was more at stake here than just her own comfort. Morgain had found her way into Camelot’s walls, and only Ailis knew. That meant that Camelot was in danger, terrible danger. She had to tell Merlin—or tell the king. She had to tell someone, somehow.

Sir Tawny sighed in disappointment, but otherwise remained silent.

“Wise girl,” Morgain murmured, passing her hand over her scrying mirror and making the image of the two figures disappear. “Wise, wise girl.” She did not know whether to be annoyed or amused by the witch-child, who had so far refused to succumb to her fears, despite being completely out of her element.

It was tempting to go to that floor, to walk with the witch-child and show her the wonders hidden therein; to teach her how to control the seascape room so that the shark would attack at her command; explain the proper way to make the wall-lights glow according to your mood; or shift the puzzle-floor so that the creatures depicted in the mosaic underfoot seemed to gambol and dance.

She could not let the girl go. Morgain considered that she could have easily killed Ailis the moment she realized someone had seen her in Camelot’s halls. She had in fact planned on it at first. But then Morgain recognized the face, those dark eyes filled with horror and surprise but no hatred. Something had made her take the girl instead—take her and keep her.

She supposed the thought had been there from the beginning: No child so filled with the potential for magic should be left untutored. Merlin had seen it and had clearly put his touch on her…but he had not taken her as a student, the foolish old man. So Ailis was still fair game.

Morgain didn’t want a student, herself. Too much effort, too much bother. But a hostage—one with potential to be useful in the long run…that was a different matter.

And so the girl was being treated more as an honored guest than a prisoner. No prisoner ever had such run of this place before—not even prisoners who thought they were honored guests. Morgain felt a twinge of regret at her actions, but she stifled it firmly. There were other brands in the fire, other considerations to be…considered.

There were others in residence who must be kept in mind. Others who would not be pleased to know of the girl’s existence.

And yet, how much harm could it do, to speak with the girl—to allay her fears, perhaps, and prevent any unfortunate and doomed attempt to escape? The process of winning her over, making her more pliable, more…useful had begun.

Yes, Morgain decided, reaching down to stroke the ears of the great black cat sleeping by her side. She would do just that—for the girl’s own good, and her own as well.

“Here? You intend for us to camp here?”

Gerard looked around in confusion at the knight’s outburst. Newt had chosen a good spot to make camp: a flat clearing a short distance off the wide dirt track they had been riding on. Surrounded on two sides by thick-trunked oak trees, with a small creek running along the third side, it seemed a pleasant enough place to stop. There was wood for the fire, water for cooking and drinking, grass for the horses to graze on, and it was far enough from the road that if travelers went by during the night, they would not be seen. In fact, Gerard had been about to compliment Newt on his scouting, as soon as he got back from watering the horses downstream.

“What is wrong with it, sir?” Gerard asked politely. His face might hurt from the strain, but he was polite. King Arthur and Sir Rheynold would expect no less from him.

Sir Caedor went off into a litany of things that were wrong with their campsite, most of which seemed to revolve around the fact that they would be sleeping outside on blankets, rather than inside on beds. Sir Caedor, it appeared, did not enjoy being outside of walls at night, especially this far north of Camelot’s reach, among people he deemed “savages and heathens.”

Gerard added all this to the list of things that Sir Caedor did not like, which so far included the way the mule had been loaded, the pace they were traveling at—too slowly, consulting the lodestone too often rather than simply aiming themselves in the general direction it indicated—the dried foods they had brought, the way that the boys did almost everything, and Newt, on principle. Newt himself had obviously been holding back laughter at some of the knight’s comments about “lowly brats” and “the stench of stable,” but Gerard was considering notions of how to teach the older man some manners.

“I’ve heard worse,” Newt told him. “From you, in fact.”

Gerard had to admit the truth of that. They had not gotten off to a good start. Their first meeting involved an exchange of insults, a fistfight, and a scolding from Sir Lancelot. But Newt had proven himself since then. He had become a friend.

None of this seemed to matter to Sir Caedor. When they had stopped to water their horses around mid-afternoon on the first day, Caedor had handed his reins to Newt and gone off to the bushes in order to relieve himself, saying over his shoulder only that Gerard should make sure that “that boy” did not take anything from his saddlebag. Yes, Newt did work in the stables, but Caedor’s casual lack of respect—due even a kitchen scullion—had made Gerard’s jaw drop in astonishment. This was not how he had been taught that a knight should behave. It was certainly not how the men who trained him would act, not even when they were in their cups during a long-running banquet, or exhausted after a hard-won tourney.

If it had been up to him, Gerard would have mounted and ridden away right then, leaving Sir Caedor’s horse tied to an old oak tree. Newt, however, had merely shrugged and picked up Gerard’s reins as well. “It’s not worth it. He is who he is. And all he sees when he look

s at me is the stables. That’s never going to change.”

“It’s not fair.”

“You’re still on about fairness?” Newt made a noise like a horse’s snort. “Grow up, Ger.”

“You shouldn’t take that sort of—”

“Gerard, he’s a knight. Annoying, yes, but no better or worse than anyone else.” Newt looked at the squire with a sort of pity. “You need to stop thinking of them as if they’re made of gold. They’re men, that’s all. Men who are very good with weapons, good on horseback, but…”

“We take a vow when we’re knighted,” Gerard protested.

“You haven’t taken the vow yet, and you’re a good fellow. Someone who isn’t…how is a vow of charity, chastity, and honor going to create something that isn’t there?”

“You’re wrong. Being a knight means something.”

“To you it does,” Newt allowed.

Gerard drew breath dramatically to retort, but a voice in the back of his head suggested that carrying on would be pointless. Gerard reached up to rub at the wound Merlin had left on his face, which still itched, and let the discussion go.

They waited in silence for the knight, then remounted and moved on.

And yet those words from hours past had been a heavy weight in Gerard’s throat since then, until he felt as though he were going to choke on it. He needed to show respect for the older man, and yet he also needed to respect the training they had both sworn to live by.

Oblivious of where Gerard’s thoughts had taken him, the knight was still talking. “All that aside, no matter that it might be the perfect location, it might indeed be the best campsite in all of Britain. But servants should serve, not make decisions.”

That was it. That was just it. Gerard had tried to heed Merlin’s words. Had tried to be polite. Had tried to hold on to the last scraps of his patience and tolerance, and respect that a knight of Sir Caedor’s years and experience deserved, no matter how he behaved now. But nobody insulted Newt except Gerard. He rubbed again at the wound and spoke his mind.

“We all serve. We were sent on this journey by our king. A journey, in accordance with the code of the Round Table, to protect and defend a damsel in need—a person under Camelot’s protection, threatened by one of Camelot’s foes.” It was as though Sir Rheynold—or even Arthur himself—had taken over Gerard’s mouth, speaking with his tongue. The emotion behind the words, though, was his own. He believed in the code of chivalry, the idea that the stronger protect the weaker. He believed in it with a passion that fueled everything he did, everything he was—everything he wanted to be.

Sir Caedor had the grace to look down, in shame, hearing that reminder of their responsibilities and obligations.

“As to your comments about Newt, you might wish to reconsider them as well,” Gerard went on. “We are traveling light, as you yourself have noted. No tents. No pavilions. No servants to fetch and carry for us. Despite what you may think of Newt, on this he is an equal to me and to you. Not a servant or stable boy.”

That brought the knight’s head back up, his cheeks burning with anger. “You dare speak so to me?”

Gerard was quaking in his saddle, actually terrified at what he was saying—and to whom. Still, the point needed to be driven home, no matter the cost. “I have no choice, Sir Caedor. This must be said.”

The knight took a deep breath, ran one hand over his thick ruff of graying hair, and stared off into the distance. His face was seamed and heavy with age, and his mouth was turned down in a frown. But he was hearing what Gerard had said. Hearing, and thinking. Gerard went on.

“If we had passed an inn last night, or tonight, or any other night, we would have stayed there.” They had to rest, and given the choice between dirt and a bed, not even Newt would choose dirt. “Have you seen any inns along the way?” Gerard asked.

Sir Caedor now looked thunderous. “No.”

“And do you know of any in the near distance that we could arrive at before dark?” Gerard knew that he was pushing his luck, but Sir Rheynold had always taught him that you needed to establish control the first time someone questioned your authority, not the sixth or seventh time. By then it was too late and your weakness was known. Arthur, your wisdom, please. Merlin, your cunning. Now would be a good time for the spell to kick in….

“There are no inns around this part of the countryside,” Sir Caedor said, spitting out each word as though it were bitter. “It’s a desolate, godforsaken land. I know this. I fought here during the battle of Traeth Tryfrwyd.”

Gerard looked around, as much to avoid yet another story of Sir Caedor’s “glorious past” as to figure out what the knight was talking about now.

Sir Caedor had a point. The lands around Camelot were fertile, even where rocky, and the trees were tall, strong things. The farther north they had traveled, fewer things grew, either cultivated or otherwise. Their destination would be, Sir Caedor claimed, even more stark; islands of barren rocks and dry soil, with nothing to recommend it, save access to the seas and a reputation for fierce fighters.

“Yes, it is barren,” Gerard agreed. “And this is the best place we saw for making camp.”

Sir Caedor did not respond.

Gerard took the silence as tacit compliance. He raised a hand as though to officially end the conversation, then turned and walked down to the creek, meeting Newt as he came back with the horses on lead ropes, the mule trailing behind on its own.

“The water cold?”

Newt shook his head, his wet hair spraying drops into Gerard’s face, as intended. “Cold enough. You should bathe, too. You’re getting somewhat ripe under there.”

Newt had declined the offer of leather chest and leg protection like the ones that Gerard wore, claiming that it would slow him down if it came time to fight or run. When the sweat began to form under the padding, sticking to his skin until it itched, Sir Caedor’s armor had to be even more uncomfortable. Gerard thought that maybe the stable boy was the wisest of the three of them.

“Perhaps in the morning, when the sun’s come up again.” He didn’t have the distrust of bathing that many of the knights and squires had, but it seemed foolish to tempt fate by getting himself wet in the cool air.

“Sir Caedor taking care of dinner?”

Gerard let out a surprised laugh. Newt and Ailis had always managed to do that; to make him laugh, even when he didn’t want to. “Somehow, I don’t think so. You want to wrestle for the job?”

“Nah, you can do it.”

“Oh, thank you.”

“Hey, I watered and fed the horses. Least you can do is feed us.”

The temptation to offer to water him, too, by throwing him back into the creek, was great, but Gerard resisted. “If I cook, you have to eat what I cook. Sure you’re ready for that?” Ailis and Newt had handled the limited cooking detail the last time they were on the road, and for a good reason: Gerard’s rabbits always came out half-raw, and the birds half-burned. He could mend armor, wield a sword, brandish a mace reasonably well, and ride a horse better than most, but he couldn’t cook.

They started walking back to the camp together, pausing to set up a picket line for the horses. A rope tied between two stakes in the ground would allow the horses to move around and graze at will, but would keep them from wandering off in the night. The mule didn’t need tethering—it was smarter than the horses, and would be fine no matter what.

“You think she’s all right?” There was no need for Newt to say whom he was talking about: No matter what other mission Merlin might have for them, no matter what the king might think, Ailis was the whole reason they were there.

“I don’t think Morgain’s hurt her, if that’s what you mean,” Gerard said slowly, finally allowing himself to speak it out loud. It was easier to worry about Sir Caedor than to imagine Ailis alone and frightened. “Merlin was right about that. Whatever reason the sorceress had for taking her, she did have a reason. And I don’t think it was just to keep Ailis from telling anyo

ne that Morgain was in Camelot. Otherwise, why not kill her right there in some way that wouldn’t raise questions?”

“Maybe she was in a hurry and needed time to do it properly?” Newt caught the look Gerard gave him, and shrugged. “It’s possible. I don’t want to think about it either, but…”

“Merlin would have known if Ailis were…hurt.” He couldn’t bring himself to say dead.

“Maybe.” Newt didn’t sound convinced. Gerard didn’t feel convinced, either. But they had to believe that Ailis was all right.

Morgain hated her half-brother Arthur. And for some reason she hated Merlin even more. But she had shown no sign of hating the three of them, even when they had stopped her from destroying the Grail Quest. Even when Ailis was urging Gerard to kill Morgain, the sorceress had seemed more amused and—perhaps—intrigued by the servant-girl who showed such affinity for magic.

That was the hope Gerard clung to, even as it terrified him. Because he knew—even if Ailis herself didn’t—how much appeal magic held for his friend. And from their brief encounter, he knew how appealing Morgain herself could be, if she decided to charm rather than oppose.

“You, boy!” Sir Caedor stood by the fire and pointed to Newt. “Gather some firewood!”

Newt made a sour face and whispered to Gerard, “If I were to pour water over his armor, might it rust shut with him inside it?”

“He’d expect me to polish it all clean again,” Gerard said in disgust. There would be time enough to go back to polishing and repairing and running errands when he was back in Camelot with Ailis safely back in the queen’s solar.

“Come on,” he said with a sigh. “Let’s go find some deadwood and give Sir Caedor a nice big comfortable fire to sleep by. Maybe, if we’re lucky, he’ll tell us some more stories about his great role in the battle of Traeth Tryfrwyd.”

West Winds' Fool and Other Stories of the Devil's West

West Winds' Fool and Other Stories of the Devil's West Gabriel's Road

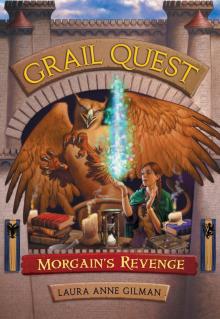

Gabriel's Road Morgain's Revenge

Morgain's Revenge The Shattered Vine

The Shattered Vine Laura Anne Gilman - Tales of the Cosa Nostradamus

Laura Anne Gilman - Tales of the Cosa Nostradamus The Camelot Spell

The Camelot Spell VISITORS

VISITORS Staying Dead

Staying Dead Silver on the Road

Silver on the Road Weight of Stone

Weight of Stone Promises to Keep

Promises to Keep Tricks of the Trade psi-3

Tricks of the Trade psi-3 Blood from Stone

Blood from Stone Soul of Fire tp-2

Soul of Fire tp-2![Pack of Lies [2] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/pack_of_lies_2_preview.jpg) Pack of Lies [2]

Pack of Lies [2] Burning Bridges

Burning Bridges The Work of Hunters

The Work of Hunters Miles to Go

Miles to Go Pack of Lies psi-2

Pack of Lies psi-2 Tricks of the Trade

Tricks of the Trade Hard Magic

Hard Magic Bring It On

Bring It On Darkly Human

Darkly Human The Cold Eye

The Cold Eye An Interrupted Cry

An Interrupted Cry Soul of Fire

Soul of Fire Hard Magic psi-1

Hard Magic psi-1 The Shadow Companion

The Shadow Companion Flesh and Fire

Flesh and Fire